Introduction

We crept through the dark, damp and dusty tunnels in Cerro Rico, the biggest silver producing mountain in the history of the world. We took a break, while a veteran miner named Eduardo chewed coca leaves.

In between bites, he told us most miners do not live until their sixties like him, because of accidents and silicosis.

We bent and twisted as walked further in the cramp passages. We were directed to a short tunnel to meet Tio (Uncle).

Tio is the god of this mine. He had a cigarette in his mouth and colas, candies and coca leaves scattered around him. Every Friday, the miners provide him with gifts, asking him for protection in their dangerous work.

Before we entered the mountain, we would have scoffed at this as superstitious nonsense. After being in there for a few hours, we knew it was a prudent strategy. All through our travels in Bolivia, we encountered such alternative approaches to living.

Our Story

After three days in La Paz in April 2018, my wife Khadija, friend Steve and I went to Bolivia’s Central Valleys to see Sucre, a marvelously preserved colonial city. Then we went back to the Altiplano (High Plains) to the hard-scrabbled mining city of Potosi and then the frontier town of Uyuni, the beginning of the largest salt flats in the world. As we travelled, we learned more about the often-tragic history of Bolivia and the intriguing cultures of the country. This was part of a longer trip to Bolivia, Peru and Colombia.

Sucre

Sucre is known as the “White City” with its bright buildings getting a yearly whitewash, such as this one across from the 25 de Mayo Plaza.

We were amazed to see block after block of the well-preserved colonial architecture and concurred the city should be an UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Sucre is the constitutional capital of Bolivia. While La Paz is the administrative center of government, the Supreme Court of Bolivia is located here.

We noticed there were many foreign young people milling around in Sucre. We found out that many attend the La Universidad de Sucre to study the languages, cultures, and history of Bolivia. There is also the University of Saint Francis Xavier, which is the second oldest university in the Americas. USFX was founded in 1624 through an order of King Philip IV of Spain.

The university was established to educate the gentry of South America in law and theology. It is now a public institution and is the main university of Bolivia since the country’s independence was established.

The Aymara women here dress differently from those in La Paz, with skirts to the calves instead of the ankles, many fewer skirt layers and fedoras instead of rounded bowler hats.

We spent a few hours in Bolivar Park watching the families, young couples and playing children. It is the largest and best-known park in Sucre showcasing sculptures and art, including a miniature almost-reproduction of the Eiffel Tower. The tower was designed by Gustave Eiffel and was shipped from France and assembled in 1908.

There are many street vendors around the park and the ice cream is famous for being the best in Bolivia.

We walked up the slopes of Churuquella hill to ASUR (Anthropologists of the Southern Andes) Museum which displayed and promoted the production and sale of high-quality indigenous arts and textiles. Inside we saw a local woman weaving.

Walking further up the hill, we arrived at the Monastery of La Recoleta. It was founded in 1601 by the Franciscans. The complex has a plaza surrounded by a primary Catholic school and a church, with a fountain in the middle.

The walk down was steep with a terrific view.

Throughout our trip in Bolivia (also Peru and Colombia), we constantly saw marching bands. This one was endearing, as the children were marching in their school uniforms.

Helping direct the parade, escort pedestrians and encourage cars to drive safely, young people dressed as Zebras frolicked and entertained while they were doing their job. They do this work throughout Bolivia and became internationally famous in a 2017 feature story on John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight.

As always, we went to the central market. As usual, the most interesting aspect was the vendors and customers.

A highlight of Sucre was staying in the Hotel Monasterio, an elegant 16th century Colonial property with a wonderful central sitting area.

After two days in Sucre, we hired a taxi to take us to Potosi. There were a few stops in between with woman selling food to the passengers in cars, trucks and buses. Here we saw a good example of the ubiquitous shaggy dog.

The drive between Sucre and Potosí takes around two and a half hours. On the way, we saw a Renaissance-style suspension bridge with six stone towers, located on both banks, crossing the Rio Pilcomayo.

It was constructed in the late 19th century under the administration of president Aniceto Arce, then finished by his engineering company after he left office. As a result, the structure is known as Puente Arce (Arce Bridge).

Potosí

Potosí is one of the highest cities in the world, sitting at 4,000 meters (13,100 feet). The city came into great wealth and fame in the mid-1500s when incredible amounts of silver was found in the mines in the mountain the city sits below. The mountain was named Cerro Rico (Rich Hill) and its huge pyramidal shape towers over Potosi.

The city thrived as the largest producer of silver in the world for centuries. Eventually, the population came to exceed 200,000. Many were native and indigenous peoples as well as African slaves and Spanish settlers. The rush for silver had the colonists taking over the homes of local families before constructing more. This has given Potosí its interesting hodgepodge of colonial and local styles. It is not as meticulously preserved as is Sucre, but has an appealing look, both forlorn and vibrant.

The city’s historic district sprawls out from the Plaza 10 de Noviembre (it seems half of the main plazas in Bolivia are name with a commemoration date). Like in other cities, we sat for hours in this main square, captivated by the ebb and flow of local life.

The majority of Potosí’s population today is Quechua. The women of this community have a unique style of dress that is different from the Quechua and Aymara women in other areas of Bolivia. Here, the women wear straw hats and dresses that go down to their knees.

Still, there are plenty of local women in fedoras made of leather or cloth.

We determined there are three must-see places in Potosi: Casa de la Moneda (Mint), St. Teresa Convent and Cerro Rico.

The Spanish overlords turned Cerro Rico silver into currency at the Casa de la Moneda. The mint started in operation in 1572 and operated until the 1950s. The process of making coins was brutal on the barely-paid indigenous workers (later joined by African slaves). The workers were known as human mules. They replaced real mules which could not stand the strain of pulling wheels in monotonous circles to power silver-processing machines and died after a few months. While doing every backbreaking task, the workers were exposed to mercury compounds and vapors which often caused a variety of ailments, often fatal.

Their life expectancy was short. Either their bones and muscles collapsed or they internal organs and systems would cease to function. An estimated eight to ten million workers died producing legal tender.

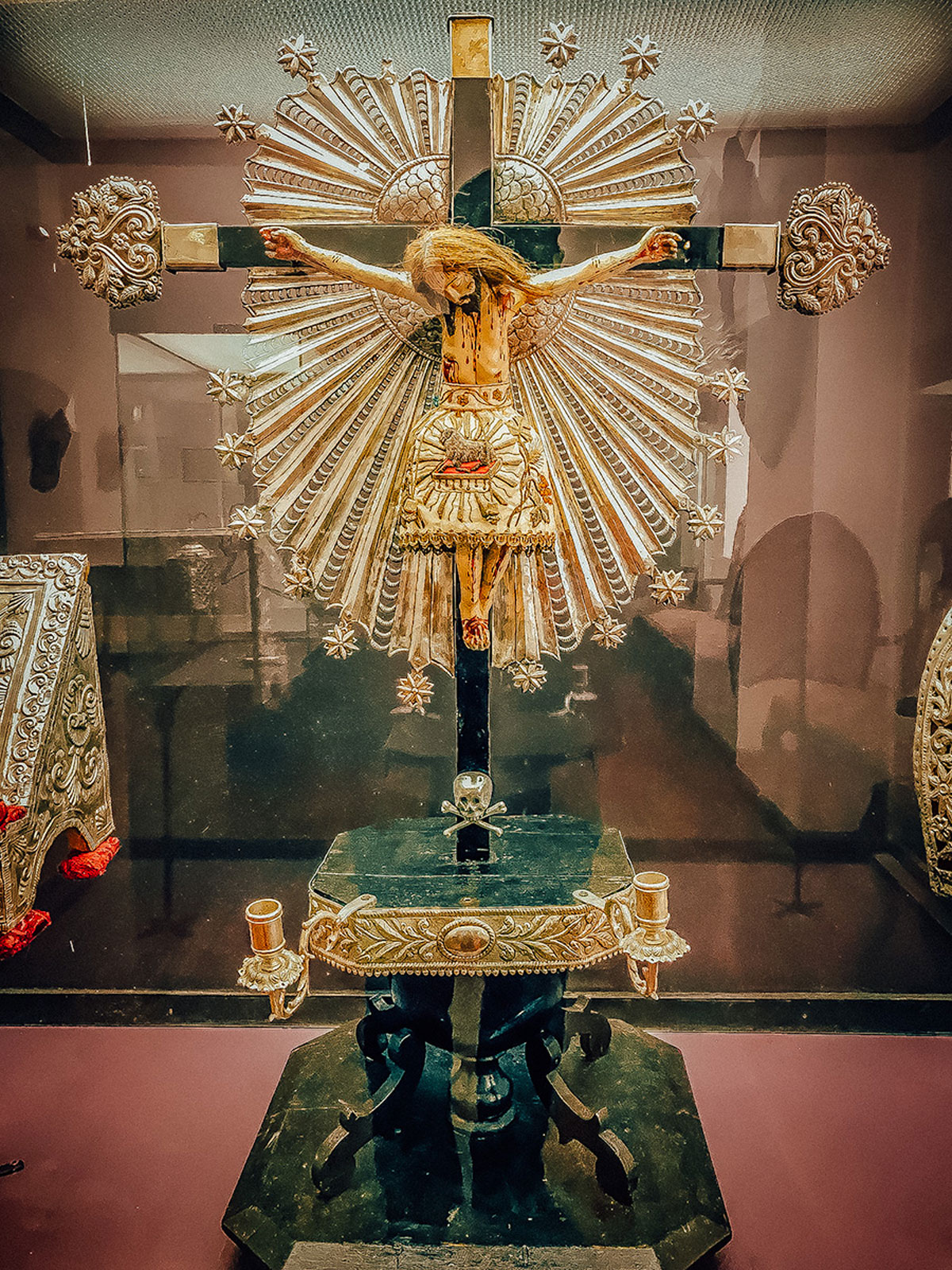

While contemplating the human suffering was distressing, we were surprised at the mint’s excellent art collections. Two items stood out to us. First there was an exquisitely crafted silver Crucifixion of Christ. I stared at it for several minutes admiring the detailed workmanship and powerful presence.

Second there was the painting Virgen del Cerro (Virgin of the Hill). The unknown and probably indigenous painter displayed the Virgin in the shape of Cerro Rico, thus mixing indigenous and Catholic beliefs.

The pear-shaped Virgin, represent Cerro Rico, dominates the painting. Around her are the Father, Son, Holy Ghost, pope, archbishop, priest, emperor, town councilor, animals, plants and the important Inca symbols, the sun and moon.

The oddest thing about the mint is the creepy face at the entrance.

Known as El Mascaron, it has become a symbol of Potosi even though the origin and the meaning are unclear.

A few blocks from the Casa de la Moneda, is the Convento de Santa Teresa, established in 1685. It has been the residence of Carmelite nuns for centuries. We were amazed to learn that in colonial times, once the nuns entered the order, they would be cloistered from the world with the exception of priests and medical doctors. They had to talk to their parents through small grated opening in the wall that prevented them from being seen or touched. There are still Carmelite nuns residing here, but since the 1960s they can participate in the outside world.

The women came from wealthy families who fabulously donated to the convent, which funded spectacular altars and artwork.

Lydia, who is completely fluent in English, French & Spanish, guided us through the multiple courtyards, gardens and rooms.

The most prominent architectural feature of the convent is the bell tower.

The most prominent architectural feature of the convent is the bell tower.

The facade of the building is made of an elegant pink stone and a good example colonial architecture modified by local styles.

For many, the sole reason to visit Potosi is to tour the mining tunnels of Cerro Rico. Steve was particularly interested as he had a great-grandfather who rose from a poor boy to one of the first non-family partners in Guggenheim Bros, then the largest mining empire in the world. We chose a local company for the tour. I do not know if they are the best, but they certainly have the best advertising poster.

Our tour guide was Jose, who worked in the mine for about five years but stopped because of health concerns. To enter we had to put on mining outerwear and a hard hat with a light.

The mines that tours go through are wet, so airborne particulates are not a worry and face masks are not necessary. Anyway, that is what we were told.

Jose told us the mines have been operating for almost five centuries. After independence, the Bolivian government ran the mine until 1985, when they transferred ownership to a workers collective. Today, there are about 200 mines in the mountain and about 15,000 miners work there. While it is not as perilous as in colonial times, when an estimated eight million died within the mountain, it is still dangerous from accidents and silicon-related illnesses.

In the main tunnels, there are carts on metal tracks for the removal of mined rock. Periodically, we would step aside as a worker pushed the carts with tons of rock by us.

As we walked, the tunnels became more irregular and narrower.

Luckily, none of us were claustrophobic but it did feel more and more confining being underground without natural light.

We saw the workers involved in extremely hard work, fueled by non-stop chewing of coca leaves. At one point, we observed drilling in action.

As mentioned in the beginning of the post, we sat by Tio to take a rest and hear about the workers’ belief in his powerful protection.

The workers need Tio’s help more than ever. Now, there is only an estimated ten to twenty years of minerals left in the mountain and the structural integrity of the mountain is in question after centuries of being hollowed out. In 2011, a sinkhole developed close to the peak of the mountain and geologists have since come out with warnings of a possible collapse.

Steve, a journalist and documentarian, wrote about our mine visit on his blog: https://stevehamm31.blogspot.com/2018/05/ghosts-of-industry-potosi-bolivia.html

The next morning, we left early in a taxi to Uyuni, a four-hour drive through mountain ridges and valleys.

Salar de Uyuni

The city of Uyuni has a circa-1880 Dodge City feel about it, with wide, dusty, dirt roads and low-rise, adobe buildings on each side. There are few trees and no sheriff in sight.

It was founded in 1889 as more of a rest-stop than a destination. However, it is the main gate way to the Salar de Uyuni (Uyuni Salt Flat), the world’s largest (10,600 square kilometers / 4,100 square miles, the size of Rhode Island).

We stayed there the first day we arrived, as we needed to arrange a tour from one of a slew of travel agents in store fronts. Khadija and I stayed in the Hotel de Sal Casa Andina, constructed with massive salt blocks.

Maybe it was the novelty, but it had a cool feel with walls and even furniture made of salt.

We stopped at three agents to get the idea of the tour cost. We quickly arranged a guide and SUV for the next day to the salt flats with Blue Line Tours. Many people go from one agent to another and haggle over the price. We paid the going rate but arranged to leave a little after sunrise so we would have the best light for photography. After finishing a surprising large amount of paperwork with the agency, Khadija and I walked around Avenida Ferroviaria to experience its public art, including statues….

…and murals.

For a time, Uyuni was a center for train repair. Evidence of this is in the Cementerio de Trenes, a train graveyard which we did not go to, but probably should have. Outside the train station on Ferroviaria, there were old trains which Khadija posed on.

It turned out we arrived on Thursday when the local weekly market occupied the streets. As always, I was enticed by the local people.

At the crack of dawn, we were picked up by Reuben our guide and driven out of town, through the village Colchani which had not yet awaken, to a salt statue park.

Reuben then took us into the salt flats. The area is the remnants of evaporated prehistoric lakes. After driving about a half-hour, we jumped out of the SUV and took reality-distortion photos. One was Khadija supporting Steve and me, symbolic of women’s role in the world.

Another one was the desert monster stomping Khadija and me.

We then drove on and saw workers shoveling salt into a large truck. They gave me a shovel to try.

Doing it once was a little hard as the truck bed was high up. The thought of doing it all day made me happy that I spend most of my time traveling the world, rather than these gentlemen who were doing really tough work.

The salt used to be shipped in horse-caravans by locals to be traded for other goods that were not available in Uyuni, like produce. Nowadays, the salt is used in construction and the lithium component in electronics.

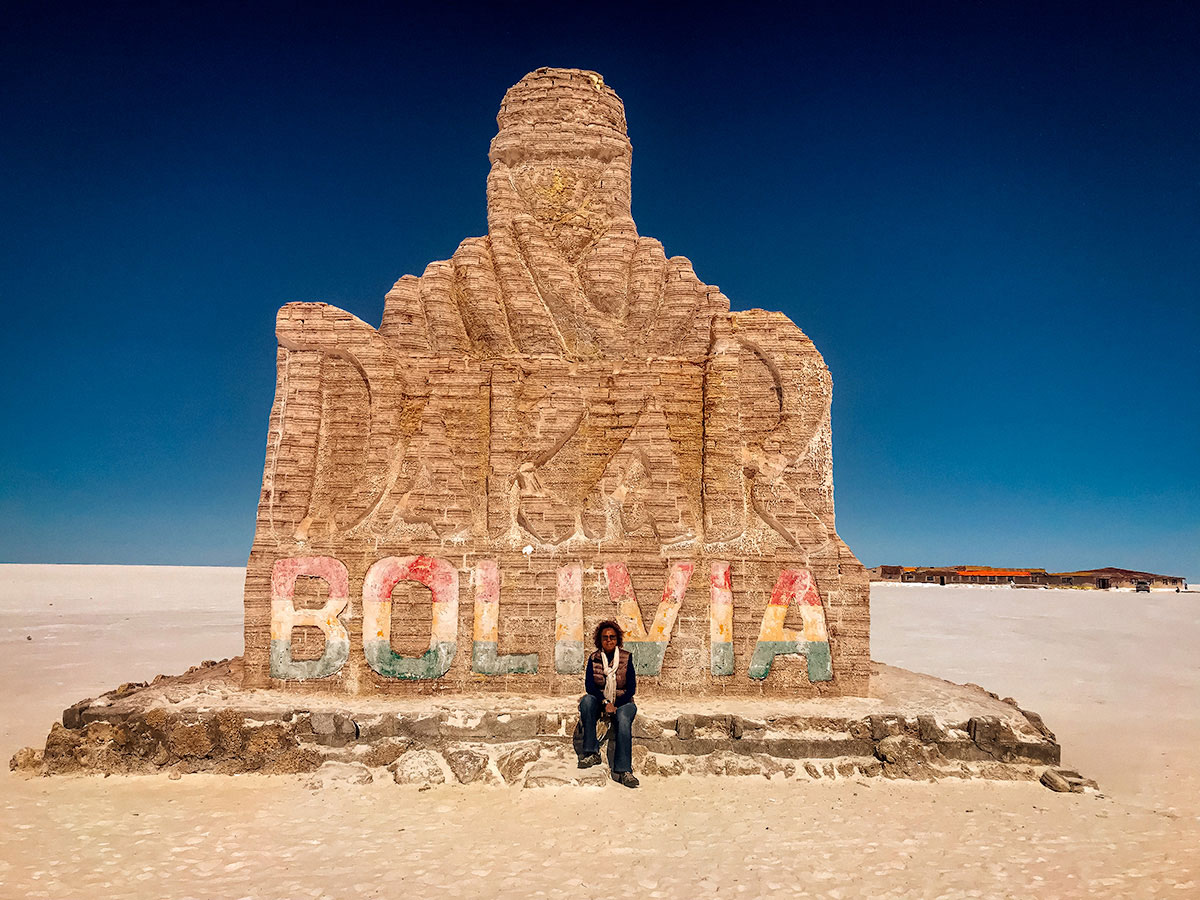

The next stop was the Dakar – Bolivia Salt Monument. The Dakar Motor Rally was moved to South America because of security threats in Mauritania and subsequent cancellation of the 2008 rally.

Close by were a collection of flags from the countries of the rally racers.

We then drove more than a half-hour to Isla Incahuasi (Incahuasi Island).

It was once an island when this was a lake, but now a rocky outcrop. It is notable for its gigantic cacti and has a tourist center.

While we were there, we walked through the cacti, around the island in the salt, and took some catnaps while the day was at its hottest.

While walking in the salt, Steve summed up his thoughts about this desolate locale.

During this time, I had long conversations with Reuben about how to operate a Nikon camera. He had similar one to mine that a Japanese man he had guided had given him.

A couple hours before sunset, we set out for the part of the flats with water, to get interesting reflecting photographs. At certain times of the year, nearby lakes overflow into the flats to make a mirror-like surface. It is a strange and beautiful landscape

I was wearing the same sun glasses as Reuben. After I inquired about his, he took us to a hardware store where they sold for US$3. I bought three, but I should have bought ten as they were excellent quality, quite cheap and I would have enough not to worry about misplacing too many.

The views in the receding light were dramatic, often catching others posing for photos.

In this amazing sunlight, Reuben, Steve and Khadija sat in the SUV and waited for me to finish photographing. Without knowing the context, they looked like undercover agents on a stakeout.

Reuben drove us to one more spot, where we saw a marvelous sunset.

From there we drove to the Uyuni airport and caught a plane to La Paz. The next day we would take a bus to Copacabana on Lake Titicaca.